The Jazz Influence on Steely Dan

The Jazz Influence on Steely Dan, or Adventures with Admiral Analog's Audio Assortment,

Part 3 of 8

Our last Listening Party featured tracks by Steely Dan and the jazz legends that influenced them. The Dan has always walked a fine line: were they rocking jazz artists? A jazzy pop band? In the end, one has to admit the musical ideology of Walter Becker and Donald Fagen was something all its own. There is no doubt however, that they were influenced by jazz legends, and the fact that they were a studio band (meaning they assembled different troupes for each album, sometimes even each song) meant that they could even work directly with some of their jazz heroes. So this blog entry will take a look back at the playlist of the last Kissa session and recap the decisions that went into creating the final selections.

Our first track was Beautiful Love from Bill Evans' Explorations (1961), a few years after he recorded Kind of Blue with Miles Davis. Evans was a big influence on Donald Fagen and the next track from our playlist, Dirty Work from Can't Buy a Thrill (1972), features some of the latter's fingering on the Wurlitzer electric piano. Our last blog entry focused on the alternative album cover for Evans' Explorations that we found at Admiral Analog.

Duke Ellington & Ray Brown, This One's For Blanton, released 1975/recorded 1973, Pablo Records

From there our playlist turned to a 1970s record from Duke Ellington's output. It is always interesting to look at a "best of" Steely Dan album and find the liner note saying "All songs by Becker and Fagen, except East St. Louis Toodle-oo, D. Ellington." The Dan wrote hundreds of songs during their partnership, but when it came to one of their idols, they couldn't find any way to modify the work and played a cover instead. True, the use of a talk box and a pedal steel guitar dramatically changed the sound from Duke's original version, but otherwise it's the same exact melody. Besides the Dan's take on East St. Louis Toodle-oo, we listened to another Ellington standard, Things Ain't What They Used to Be. But rather than hear the original, we took in a new twist made with Ray Brown in 1973 (the year before Steely Dan released their own homage.)

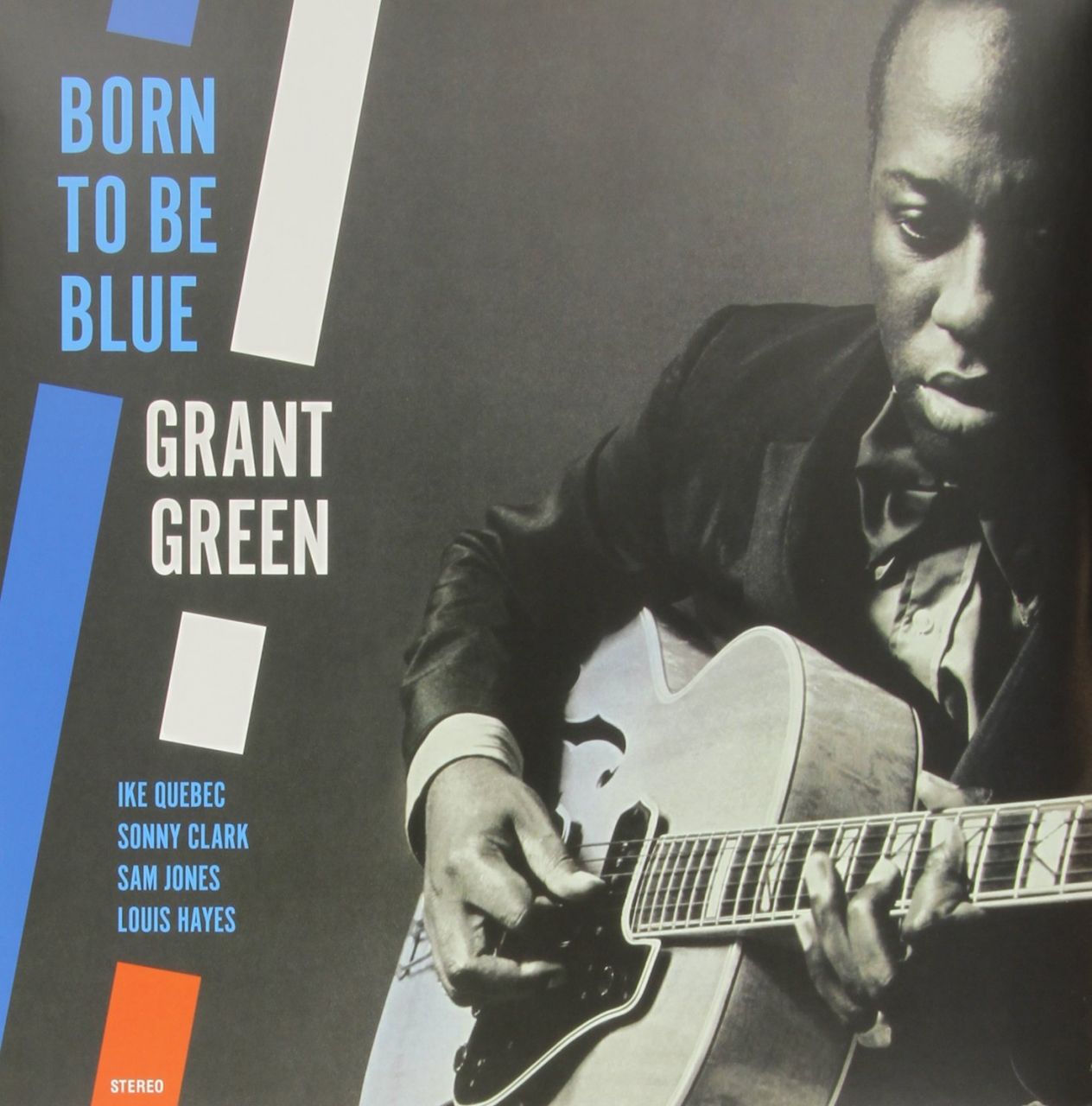

Grant Green, Born to Be Blue, 1962, Blue Note Records; 2013 Jazz Wax Records

Next we turned from Fagen's piano to Becker's guitar. Grant Green was perhaps Walter Becker's favorite jazz guitarist, so we listened to a Green blues track, Cool Blues, that featured some inspired picking. There were many great songs to choose from on Born to Be Blue, but Cool Blues was a great choice for two reasons. First, it never appeared on the original pressing and was only included in the reissue released by Jazz Wax Records that we brought to the session. Second, Cool Blues was written by Charlie Parker, who was another huge influence for the Steely Dan team, but an artist we didn't have time to listen to during the party. But since the point was to draw comparisons through guitar, we paired that song with one where Becker gets to jam himself, notably at the end of My Old School, from the 1972 album Countdown to Ecstasy.

Steely Dan, Countdown to Ecstacy, 1973, ABC Records

Being that this blog usually focuses on album art, it is worth pausing here to talk about the woman who designed the above album, Dorothy White. She was dating Donald Fagen for a few years and their relationship was at times also a collaboration. Steely Dan, unlike many of their contemporaries, had a great deal of artistic control in the production of their records, but White's watercolor for Countdown was met with resistance by the executives at ABC Records. The supposed controversy involved the fact that White originally painted only three figures and the band at that time had five main members. To compromise, she painted two more figures on the left side of the composition, though upon a long look one can tell they seem like an afterthought. The three figures on their own sum up the diverse directions any Steely Dan album seemed to take: one person looks worried, one looks bored, and one smiles back at us, almost as if they know something we don't. The following year, White also took the photograph of a katydid that became the image for 1975's Katy Lied, which we just didn't have time to get to during our listening session.

Steely Dan, Katy Lied (1975)

But back to piano. Joe Sample was the pianist in the important quartet The Jazz Crusaders, who gave us some of their most important recordings from the late 1950s through the 1960s. We heard one of Sample's compositions, Blues Up Tight, from a live recording of the Crusaders in 1966, included as part of a Blue Note re-issue series covering many different sessions from the 1960s.

By the time Steely Dan was ready to record the album Aja in 1977, they had asked Sample if he would join them for a few tracks. We listened to two songs in a row from Aja, in which Sample plays the Hohner Clavinet on Black Cow, and the electric piano on the song Aja. He was joined on the latter by a titan of the jazz saxophone, Wayne Shorter. Mr. Shorter had already been a part of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, wrote tunes and played for Miles Davis in his Second Great Quintet, and by the time of Aja was touring with his influential fusion group The Weather Report. He supposedly had to be asked several times by different musicians who could ultimately vouch for the Steely Dan sound before he would commit to a recording date, but his solos on the song Aja prove that he seemed to be at ease with the material Fagen and Becker had written for him. As with Joe Sample, we turned to the year 1966 and played the title track from Shorter's Adam's Apple so that we could really experience the saxophonist "stretching out."

Wayne Shorter, Adam's Apple, 1966, Blue Note Records

The night concluded with the album that marked the end of Steely Dan's fabulous decade of dominance during the 1970s (though by no means signaled an end to their recordings). We jammed to Time Out of Mind from 1980's Gaucho, and though the night was a great one, there were a lot of items we just couldn't squeeze into an hour. Take for instance, the fact that the title track from Gaucho borrowed so heavily from jazz pianist Keith Jarrett's Long as You Know You're Living Yours that he was eventually given co-writing credits. Or what about the fact that the first bars of Rikki Don't Lose That Number are the same opening from Horace Silver's Song For My Father? And how come there was no Mingus played? Steely Dan was obsessed with Mingus!

Well, perhaps that's for another listening party...